I am pleased that with Common Worship the Church of England has claimed a ‘season’ for Epiphany. The central theme of the manifesting of the light of Christ to the world is no longer restricted to the Feast of the Epiphany but rather is continued as a theme through the Baptism of the Lord, the Calling of the Disciples, the Wedding Feast at Cana of Galilee (year C) and the Presentation of Christ in the Temple at Candlemass.

If you drop a stone in the middle of a pond the ripples move steadily outwards in all directions. The Incarnation of Christ was the central event whose ripples are still radiating outwards in time. We are still struggling to understand the full implication of the mystery of the Incarnation and so we must continue to move outwards towards new ways to understand both our fellow creatures as well as the creation itself. This means that as the Baptised we must explore the full implications of our humanity and the redemption of it. This involves a constant vigilance against labelling others as a way of deciding that we already know all we need to know about them. We need to study and learn about all of the cultures and expressions of humanity on the planet. Needless to say this is not primarily an endeavour of the mind but rather the heart. We strive to recognise Christ in one another. The wise men from the East, which are usually depicted representing the three ‘races’, are a symbolic of this.

As cliché as it might be, it is worth remembering that in the Christian world the idea that the Incarnation has given such a dignity to every human being that it is obvious that we should neither own other human beings nor trade or sell them is a relatively recent realisation. The same goes for the place of women in our society, although it is important to remember that his is still not the case in many societies of the world - many of them Christian.

Yet crude stereotyping still abounds. All of you know some dinosaur like men who remain misogynistic and think that jokes about women are still funny. I have heard gay men make anti-Semitic remark as well as repeating crude stereotypes of the Romani. The issue of modern day persecution and stereotyping (Antiziganism) of the Romani is one of the more complicated social issues in Europe and one I cannot cover here. It is worth noting, however, that Antiziganism has been rife in Europe since the 13th century, the owning of Romani slaves in parts of Eastern Europe was only abolished in 1885, that it is estimated that one and a half million Romani were exterminated by the Germans during the Second World War, the sterilisation of Romani women in Czechoslovakia only ended in 1989, and the issue of basic human rights for the Romani is a major political issue today. The repeating of negative stereotypes about an actively persecuted people is simply dangerous. The irony of a gay man doing it is distressing. I assume most of you know that the Third Reich tried to wipe three groups of people from the face of the Earth: the Jews, the Romany, and homosexuals. The Nazis’ convinced the general population of the danger of these three groups by the use of extreme stereotyping. I would hope that if all three groups shared the same suffering in the concentration camps as well as the same fate, then we would at least feel enough solidarity to protect each other or at least refrain from repeating negative stereotypes. I said to one gay man who objected to my criticism of such stereotyping because the stereotypes were ‘true’, “sure stereotypes are not in the least bit destructive you effeminate faggity sodomite” - or at least something like it. Upon reflection I realise I should have used the label ‘predatory paedophile’.

I recently got into the old debate with a friend about Sikh RCMP Officers wearing their turbans. I want to point out that those who claim that the turban is not part of the Sikh religion but rather their cultural are incorrect. Whilst it is true that it is the wearing of uncut hair that is found as one of the Five Ks, Sikhs follow the teaching of the Ten Gurus and it was the tenth Guru Gobind Singh who directed that turbans be worn (although it was common since the sixth Guru) to protect the hair and the sacred comb – another of the five Ks.

By the beginning of WWI twenty per cent of the British Indian Army was made up of Sikhs and by the end of WWII held the highest number of Victoria Crosses awarded per capita. In 2002, the names of all Sikh VC and George Cross winners were inscribed on the pavilion monument of the Memorial Gates on Constitution Hill next to Buckingham palace. During World War I, Sikh battalions fought in Gallipoli , Egypt, Palestine, Mesopotamia, and France. Several Sikh Regiments were raised in World War II, served at El Alamein and in Burma, Italy and Iraq, and won twenty seven battle honours. Sir Winston Churchill said of them:

"British people are highly indebted and obliged to Sikhs for a long time. I know that within this century we needed their help twice and they did help us very well. As a result of their timely help, we are today able to live with honour, dignity, and independence. In the war, they fought and died for us, wearing the turbans."

General Sir Frank Messervy, GOC (General Officer Commanding) of the Indian Army said:

"In the last two world wars 83,005 turban wearing Sikh soldiers were killed and 109,045 were wounded. They all died or were wounded for the freedom of Britain and the world, and during shell fire, with no other protection but the turban, the symbol of their faith."

The rich and ancient history of the Punjab and the Rajputs aside, it seems to me that the Sikhs have more than earned the respect of the Western world (not that it should have to be earned as most students of history and world culture would have already given it). They are right to expect that their traditions would be respected and understood to be part of our history as well. It is a painful irony that for Sikhs the turban represents their commitment to the universal nature of the human family whilst for many in our society it is a sign of their ‘otherness’.

Those who argue against the allowing of Sikhs to wear a turban is that it prevents them from wearing a Stetson hat on the rare occasions RCMP officers wear their red serge dress uniform. The wearing of the Stetson seems to be seen as a crucial symbol of Canadian identity. Although the RCMP were not founded until 1920 the uniform is taken from the Royal Northwest Mounted Police founded in 1875. However the Stetson was not part of the uniform. They wore pith helmets. These helmets were considered impractical on the windy plains and so the Stetson was adopted in 1904. It seems odd to me that a hat adopted for pragmatic use about a hundred years ago, and now worn infrequently should be considered of such importance. This is especially true when the entire uniform is based on British military uniforms which were also worn by Sikhs throughout the Empire. Needless to say, I cannot see how the history and importance of the two head coverings in question are even remotely comparable.

The thing I admire most about Canada is her dedication to what is called the ‘mosaic’ model of multiculturalism as opposed to the ‘melting pot’ model used by our neighbour to the south. This is not really correct though as the Canadian way is really more ‘integration’. As Andrew Potter says in his November 8th MacLean’s article ‘Canada has never offered a Mosaic’:

“.. the Queen’s political scientist Will Kymlicka, .... smartly observed that while Canada was not assimilating immigrants, it wasn’t offering a mosaic either. Rather, the institutions and policies we had designed were aimed at the middle path of successful integration: allowing newcomers to keep as much of their cultural traditions as possible, while providing the means for their full participation in civic life. The classic example here is the debate over the Sikh Mountie who asked for permission to wear a turban instead of the usual stetson. While the idea made assimilationists want to chew leather, they failed to understand that the whole point of permitting the turban was to integrate the Sikh community into one of Canada’s most visible and important institutions. The alternative—banning the turban—would have the perverse effect of alienating the Sikh community from the national police force, contributing to the very cultural isolation that assimilationists claim to abhor.”

Thus I was distressed to see that the Angus Reid Public Opinion Poll on ‘Mosaic or Melting Pot’ published at the beginning of November shows that support for this policy is eroding away.

“For decades, the concept of the mosaic—where cultural differences within society are deemed valuable and regarded as something that should be preserved—has been used to establish a difference between Canada and the United States. Americans consistently refer to their country as a melting pot, where immigrants assimilate and blend into society.

More than half of respondents (54%) believe Canada should be a melting pot, while one third of Canadians (33%) endorse the concept of the mosaic. The melting pot is particularly attractive for Quebecers (64%), Albertans (60%) and respondents over the age of 55. The mosaic gets its best marks among British Columbians (42%) and respondents aged 18 to 34 (47%).”

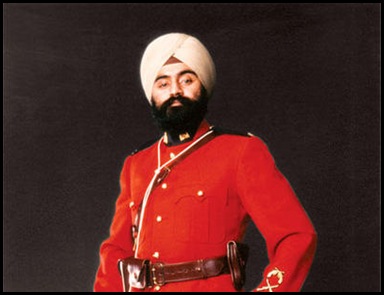

We have made huge strides in the West towards understanding one another and learning to celebrate human diversity – just look at the huge gain in the rights accorded to gay people since the Stonewall Riots of 1969 (although there is still a long way to go we too often forget how much has been accomplished in such a very short period of time). Yet there is still a long way for us to go, let alone the rest of the world. I have written at length before about the anthropology of clanism and religious fundamentalism as a response to the sudden emergence of globalisation. So it will suffice to say here that the fight to continue to educate ourselves about one another is of crucial importance at this point in our history. Canada can be a beacon of light as a successful template for how multiculturalism can really work in this rapidly changing world. I look to a Canada comfortable with her immigrant history as well as with the history of her more recent immigrants and not threatened by it. For me the sight of RCMP Sergeant Baltej Singh Dhillon in his dress uniform wearing his turban is the perfect symbol for the Canada I admire and want to see flourish. It speaks of a breadth of understanding of human culture and history and a challenge to provincialism.

The ripples of the Incarnation continue to move ever outwards as the divine light of the Kingdom of God continues to rise higher and higher shedding light on the world and her peoples. It will continue to rise until we recognise in one another the image of Him who came into the world. As Jean Vanier reminds us:

“The Word became flesh so that flesh can become Word.”

In the light of the Epiphany we are able to see clearly – all humanity (Adam’s humanity East of Eden as Saint Barnard of Clairvaux reminds us) has been sanctified. In the light of Christ there is no us and them, there is only us – those for whom he came and for whom he died.