SCHOLARSHIP OF SAINT BASIL THE GREAT 2012

Let me tell you about a 2nd class Indian Rail coach. Indian trains have an elaborate and complicated class system; 1st AC (which most trains do not have), 2 Tired AC, 3 Tired AC, AC Chair, 1st Class, Sleeper, and finally 2nd class. Everything above 2nd class has to be booked ages in advance for reservation. I will not even begin to explain the complexity of the numerous types of tickets available and the different types of wait listing. There is no 3rd class. I found travelling 1st AC challenging but perhaps that was because it was an almost three day trip.

As a result of a a complicated set of events I will not go into, I found myself on a train in an isolated area with the choice to move to 2nd class or get off the train at the next stop and be stranded. And I really mean stranded. The system of hotels, taxis, buses, and airports a westerner takes for granted does not exist in most areas of India. Even a short distances of 30 kilometres outside of westernised areas like Bangalore is like stepping from the ‘1st world to the stone age’ as William Dalrymple puts it. I decided to move to 2nd class. Did I mention it was a 38 hour trip?

It was a 38 hour trip.

Simply put I have never experienced anything like it in my life. To say it was crowded is such an understatement as to be absurd. I was one of the lucky ones as I had a seat and for much of the trip, thanks to a kind Sikh, a window seat. Seats designed for four people held nine or even ten. The wire luggage racks overhead were also used by people for sitting or sleeping and parents would stick their small infants in them. Literally ever available space on the floor was also used to cram people into. There were even people crammed in under the seats.

It soon became obvious that this was going to be an endurance test like no other. I could only drink small sips of water just to keep my mouth from cracking because to drink very much would mean eventually having to make my way off the train at a stop to urinate and then get back on (my seat would have then been taken). I saw some people somehow swinging down the aisle placing feet on people’s shoulders and heads whilst clutching luggage racks overhead. I knew I did not have the wherewithal to accomplish that monumental feat.

At one point during the night I realised that I had at least six people using me as a sleeping aid: two on the seat opposite had their feet on me or shoved under me; one had his head on my leg whilst another slumped over him onto my shoulder; two were on the floor either on top of my feet or under my seat pressed against my heels. The count is seven if you count the man asleep above my head on my bag in the luggage rack drooling on me. There was no way to move even a little as if you sat forward in your seat you would then be unable to sit back again.

I think the reality of the poverty really hit me when I watched a rat scurry in and out amongst the people on the floor and across the lap of an elderly woman. She did not move and no one else even blinked. Arundhati Roy, in her 1997 Booker Prize winning The God of Small Things, speaks of this quiet resignation.

“But when they made love he was offended by her eyes. They behaved as though they belonged to someone else. Someone watching. Looking out of the window at the sea. At a boat in the river. Or a passerby in the mist in a hat. He was exasperated because he didn’t know what that look meant. He put it somewhere between indifference and despair. He didn’t know that in some places, like the country that Rahel came from, various kinds of despair competed for primacy. And that personal despair could never be desperate enough. That something happened when personal turmoil dropped by at the wayside shrine of the vast, violent, circling, driving, ridiculous, insane, unfeasible, public turmoil of a nation. That Big God howled like a hot wind, and demanded obeisance. Then Small God (cozy and contained, private and limited) came away cauterized, laughing numbly at his own temerity. Inured by the confirmation of his own inconsequence, he became resilient and truly indifferent Nothing mattered much. Nothing much mattered. And the less it mattered, the less it mattered. It was never important enough. Because Worse Things had happened. In the country that she came from, poised forever between the terror of war and the horror of peace, Worse Things kept happening. So Small God laughed a hollow laugh, and skipped away cheerfully. Like a rich boy in shorts. He whistled, kicked stones. The source of his brittle elation was the relative smallness of his misfortune. He climbed into people’s eyes and became an exasperating expression. What Larry McCaslin saw in Rahel’s eyes was not despair at all, but a sort of enforced optimism.”I have seen great poverty in different parts of the world but never at such close and intimate proximity for such a prolonged period. I began with an ‘escapist’ portal in the form of Kipling’s Kim which I still had four chapters left to read. However, a physically malformed young man was getting off at the next stop and was unable to reach his bag. He did not ask for help but kind of looked around hoping for help and when none came he just kind of stared up at it hopelessly. It was the hopelessness of the stare that made me jump up and push my way to where he was to get the bag for him. In so doing Kim, and my only escape, flew out of the window and into the night desert of Rajasthan.

I was very patient and even calm and although I feared that claustrophobia, panic, irritation, anger, or an emotional empathy for the poverty I was immersed in might arise unabated in my breast nothing awoke. However, that hardly means I was unaffected. I became painfully aware that what separated me from those around me was not money, or privilege, or the country I either come from, was educated in, or live in. It was something born of all three and more. I have a voice. One that can be heard above the din. Another way of saying this is that I can expect to be noticed. Those with whom I was travelling had been silenced and not just metaphorically. The blank staring looks, the lack of interaction, the indifference to surroundings, the lack of expectation of any level of comfort or human dignity all silently spoke of it.

At no time did I feel in the least bit threatened or unsafe. I guess I do not really mean me personally as it is unlikely that a male western tourist will be harassed on a train. What I mean is that, even with all the shoving and pushing to get on or off the train, or to climb over one another I did not feel or see any signs of hostility, anger or irritation. Everyone seemed calm – almost comatose. Yet at the same time I was more than aware that this seemingly ‘quiet’ or ‘resigned’ poverty can, when aroused from its sleep be capable of acts of extraordinary anger and violence of the kind that can change history.

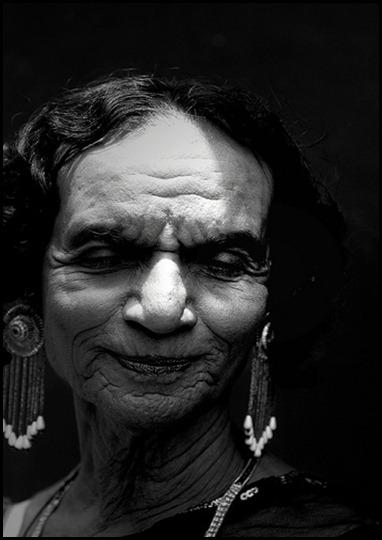

The thing that stuck out was a part of India that I think is mostly hidden from most tourists. Local beggars, cripples, musicians, hawkers of everything under the sun and holy men would get on at one stop and move along the carriage to get off at the next stop and start the process again. It was fascinating. Yet the most interesting was the Magic Transvestite.

To be fair to the culture, Indians refer to them by their Urdu (from an Arabic root) name Hijra. They are a traditional part of south Asian culture. They are men who dress and identify themselves as women who live in community under a guru and are usually considered and classified as a third gender.

They are mentioned in the Karma Sutra and in both the great Hindu epics. In the Ramayana Rama orders all the men and women that have followed him into the forest before his fourteen year exile to Ayodhya to cease to grieve for him and return home. When he returns fourteen years later he discovers that the Hijra, being neither male nor female, had stayed in the forest. So impressed was Rama by their faithfulness that he gave them the power to bestow blessings.

In the Mahabharata Lord Aravan gives his life to the goddess Kali so that the next days battle may be won. His only wish is that he marry. As no women will marry a man who will die on the morrow the god Krishna disguises himself as a woman and marries him. An eight day feast at the Temple of Aravni in Tamil Nadu every year celebrates this marriage.

Hijra are often encountered in the streets or on trains going around offering blessings and it is widely believed they have the power to do so by more than just Hindus. The Hijra that spent time in my train carriage was sought after for blessings by Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims (at least the three faith adherences I could identify by sight). They are a regular part of Indian wedding and birth rituals and parties.

What will forever stand out in my mind though is that this Hijra sounded EXACTLY like Harvey Fierstein only in Hindi! I know many of you will think I was imagining it because Mr Fierstein played a drag queen in both La Cage aux Folles and Torch Song Trilogy (both of which he wrote). But it was the coincidence that blew me away. First I heard the voice calling out for blessings. I thought something like “gee that sounds like Harvey Fierstein” and then a holy transvestite climbs into view. Once you have Mr Fierstein’s voice you cannot mistake it for anyone else’s. For those of you who do not know what he sounds like here is a random clip from the internet that is NOT of him receiving an award of some sort. The second a bizarre song sung on Sesame Street. I have a hard time figuring out how they managed to get him to sing it without anyone realising the possibility of anti-Semitism allegations. Really, a song about noses called ‘Everything is Coming up Noses’ sung by an Ashkenazi New York Jew in which he shoves noses onto everyone?

Anyway, it just goes to show how different the world can be. A transvestite in Western culture would never be treated with religious awe let alone respect. I need not mention the history of persecution by western religions. I will also not get into Jungian concepts of the Sacred Hermaphrodite in pagan and classical religion but simple point out that the concept of a third gender is common to most cultures. Just not ours.

Still wouldn’t it be a different church if instead of persecuting transvestites we hired them to give blessings on a Sunday? And, hey, no jokes about men already dressing up in coloured ‘dresses’ every week to do just this! I know that transvestites are not the same as drag queens (the later are entertainers) but my mind immediately jumps to finale of Pricilla Queen of the Desert (the depictions are of indigenous Australian animals and the Sydney opera house). There are few church services I have been to that could not have benefitted immensely from a drag queen blessing thrown in at some point (for those of you who lack a subtle sense of humour I would like to gently point out that I am being farcical here).

To return to my main point, a couple of things became clear for me during that 38 hours in a second class Indian train carriage. One, is that I realised that the India I love is one typical of scholarly bookish types like myself. I Have always loved the ‘idea’ of India. The great sweeping epics, the Vedas, the ancient civilisation with its art and architecture. The philosophy and religious traditions that have so enriched the world. The treasures of mystical metaphysical poetry of the Sufis and Sikhs. That India I have not encountered. Only remnants of it. The left over shells of what once was. As a metaphor, Buddhism works well. The Lord Buddha was Indian and his entire ministry was within India. The great ancient monuments associated with him such as Bodh Gaya, Sanchi, Sarnath, the caves at Ajanta or Ellora are all in India. And yet Buddhism all but died out in India by the 13th century leaving nothing but remains and even these were forgotten until the modern era.

The India I have harboured in my breast all these years no longer exists any more than the Israel of the Patriarchs and the Prophets or the Athens of Socrates. Then again neither does the Deep South of my childhood or the Scotland of my formative years. Yet at least these places today are still are somehow ‘mine’ and I can relate to them. India, like modern Israel and Palestine or modern Greece is simple foreign, maybe not intellectually, artistically, or historically but culturally. Yet still I feel that the India of the Upanishads or the Lord Buddha that ‘was’ is still part of me just like the Greece of Plato that ‘was’ and the Jerusalem of the Apostles that ‘was’ are also. Of course I am not surprised, and this is not something that I did not already know. What is different is the resignation to it that hung so heavily on me.

I believe a few decisions were made for me then. The first is that I realised it is an illusion when I tell myself I want to minister for periods in India or Africa or Asia. Actually I don’t. I like the idea of it but the stark reality of multi-faith settings, poverty, the heat, the crowds, the lack of resources shows it up for a vision of self delusion. I am now quite sure that I would like to spend my remaining years not just in the West but also, as I have done for the last 27 years, in the north where the springs and autumns are crisp and the winters cold and the people few.

The Christianity I have encountered in these places is also alien to me. It has a confidence and a missionary zeal that I find, frankly, frightening and somewhat repulsive in its arrogance. I have found myself on quite a few occasions in some of my more adventurous travels sitting in church or speaking to Christians and thinking that what I was hearing was not just wrong, but destructive and quite dangerous. A great deal of it I have simply found to be superstitious and really a type of folk magic. One service I attended here in India was the biggest bucket of crazy (the exact phrase I used when asked by the leader how I liked it) that I have every encountered. I will only say it is the only Christian service I have every attended where there was no reading from Holy Scripture and the Lord’s Prayer was not said. The theme, by the way, was about the signs in the news of the end of days and the demons in the people around us.

Yes, evangelical Christianity is growing, yes it has huge numbers of people. Still, by and large, it is not something I want to be associated with. I also know I have nothing to say to it. I am a product of fallen West and have been trained as an apologist and as a laudator temporis acti (praiser of the things past). The Anglican Church that I love no more exists today than the India of the Lord Buddha. Yet there is a difference. I personally experienced the last of the old style High Church Anglicanism of the British Isles and have continued to try and carry what is best in that tradition into the present. The Anglicanism I witness too does still exist in the sense that I still exist and minister.

My frequently used metaphor of the modern West is of us being a dazed group of people slowly picking our way out of the crater created by the fall of West after the second World War. I am part of the chain of people picking through the rubble seeking to save what can be saved and pass it on to future generations in the hope that it will be of help or at least add a bit of beauty to future generations. I am a product of the fall and the kind of faith and religion I adhere to only makes sense in a post medieval, post Christendom, and post-modern world. It is a ‘second tier’ type of religion if you like. It does not translate to an earlier stage, and I am almost certain, is also of little use for converting those who have lost a the basic Christian interpretive base and become wholly secular. I am well suited for this middle bit which is the time and culture in which I currently live. I am what I am - a Christian apologist during the the end days of the delusion of Christendom. So I am now almost positive the rest of my ministry will be spent in the West, if only because I would have no voice anywhere else.

One last thing that became obvious to me, that again I already knew. I need time to myself and retreats at monasteries and living alone are quite alright for me. However, I think the time of travelling alone needs to come to an end. The world is fascinating. People are fascinating. But the joy of travelling is to share the experience. It is somehow empty without someone else around, even just at the end of the day to chat with over supper. I have seen enough of the world now that I could quite happily never go anywhere new again. Not that I will not. But I think from now on, if I can not get someone to travel with me, I shall try and join others where they might already be going (if they will have me) or travel to where I already know people. In the worst case scenario I shall save my money and travel ever three years with the University of Cambridge’s Alumni group. You get an actual Cambridge Fellow leading the trip wherever it is and whatever it its theme is - Architecture of the Lower Rhine Valley or Early Mayan Civilizations for example. So you get an academic course, a professorial tour guide, and presumably interesting (or mind numbingly boring) fellow tourists.

I cannot do this again. I feel ok, but I can count the conversation I have had over the last three months on two hands. I have spoken to my father maybe three times, to an Englishman one afternoon over a cup of tea, a German for three days, a North Indian Bishop and his English wife over Sunday brunch, and another Englishman for a day out in Munnar.

I was told by my Sanskrit professor at university about the famous Hindu scholar R.C. Zaenher’s first visit to India (although knowing Zaenher’s history as an MI6 Officer it seems likely that the story is apocryphal). His brilliance as a philologist enabled him to study not only Sanskrit but also Pali and thus read the ancient texts of India and become one the of the foremost experts on Hinduism in the world. However, he had never been to India. Finally when he was elderly he agreed to give a series of addresses in India. After his arrival the local dignitaries took him to a nearby hill cave temple of Lord Ganesha. So Professor Zaehner climbed the hill, walked into the shrine, took one look at the ghee and milk covered lingam, saw the rats drinking from the Yoni, smelled the curdled milk mixed with flowers and heavy incense, turned around walked out of the cave, and vomited. He never wrote about Hinduism again. I was worried about having a Zaenhner expereince and yet now that I have I feel freed by having my world be thrown back upon itself. Instead of the prospect of an ever increasingly syncratic and exapanding indentification with other cultures to the point of dissipation I feel I can begin to re-incarnate where I am. To put this in a less convoluted way, I have travelled far enough out to not feel the need to keep going but to be happy to return to where I started and be, with God's grace, more settled.

I have always dreamed of coming to India. I am honoured to have spent time with the Saint Thomas Christians and feel privileged to have been able to see what I have and to be able to go on the ‘grand tour’ of ancient sites that I embark upon next week. Yet the reality is that it has, instead of being transformative in a new direction, rather been an exercise in exorcism. Many of the ghosts of uncertainty and doubt I had about my life and ministry have been laid to rest. I find myself much more confident of the decisions I have already made in my life, the path I have vowed myself to, and the lifestyle I have embraced.

Now I really just want to go home. How nice it will be to: breathe fresh air without stench; or drink a clean, cool glass of water without worrying about getting sick; to brush my teeth using the tap; to sleep without earplugs; to be somewhere clean without rats and mice or roaches; and most of all to be able to talk to someone.

Only seven more weeks.

POST SCRIPT: I did become ill after the 38 hour trip. I also, three days later, to avoid travelling 2nd class again spent almost $300 to travel 160 kilometres in a taxi to Mumbai to purchase a one way plane ticket to Kerala. So I do not discount the fact that having money is the same as having options.