SCHOLARSHIP OF SAINT BASIL THE GREAT 2012

The metropolitical jurisdiction of the Church of the East in India is officially named the Chaldean Syrian Church. It primarily exists in the city and surroundings of Thrissur. It’s present origins begin in 1796 when the Maharaja of Cochin, Shakthan Thampuran, brought fifty two Christian families from around the State to settle in Thrissur. The church for them was built in 1814 and consecrated the following year by Father Abraham Palai who, as directed by a Royal Charter of the Maharaja, used the “Chaldean Syrian Rite”. This is the origin of the name of the church.

Until the coming of the first bishop in 1861 there seems to have been no continuity of ministry in Thrissur. There are records of a Chaldean priest, Father Denha Beriona, visiting and conducting services in 1849 but besides this it is surmised that the Christians in Thrissur visited the neighbouring churches in Ollur and Aranattukara for services and borrowed priests to come to Thrissur to conduct services.

The Chaldean Patriarch Joseph Audo VI played a significant role in the history of the East Syrian community in Thrissur. He had a long and bitter feud with the Vatican and at various times during his Patriarchate was threatened with excommunication and other ecclesiastical sanctions. More often than not it was hard to tell whether he was ‘in revolt’ and thus renegade or ‘in good standing’. The Most famous acts of disobedience being: in 1860 his agreement to send a Bishop to India in spite of the protest of the Apostolic Delegate Henri Amanton; in 1870 his passionate opposition to the doctrine of Papal Infallibility, his refusal to accept it and his political machinations with the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire against the Vatican over it; and in 1874 when he sent Mar Mellus to India without permission from the Vatican which resulted in Mar Mellus’s excommunication. Each of these acts of disobedience was eventually resolved by forcing his submission using fierce pressure from the Vatican. When he died he was, once again, reconciled with Rome.

His first influence on the church in India began with the arrival of Mar Roccos in 1861 whom he sent to India at the request of East Syrian lay leaders who wanted a bishop. Mar Roccos was opposed by Father Kuriakose Elias Chavara, the founder of the Syrian Romanist congregation Third Order of Discalced Carmelites which later became CMI - the Carmelites of Mary Immaculate.

He had ascertained that Mar Roccos had not been sent by Rome but rather by the renegade Chaldean Patriarch. The Vatican successfully brought enough pressure to bear on the Patriarch for him to agree to withdraw him. Mar Roccos was forcibly put on a boat at Cochin and sent back to Mesopotamia. With him went a young priest Father Anthony Thondanata, who jumped on the boat as it was settling sale. He was encouraged to sail with Mar Roccos by resentful laity who still desired an East Syrian bishop. They hoped he could help ensure the survival of East Syrian Christianity in India by lobbying for another East Syrian bishop to be sent to them. When the Patriarch declined to consecrate Father Thondanata or anyone else as a bishop for India out of fear of further antagonising the Pope, Father Thomdatta sought out the Catholicos-Patriarch of the Church of the East, Mar Rewil Shimun, who consented to consecrate him as Metropolitan of Malabar and India.

Anthony Thondanata, now Mar Abdisho, returned to Cochin in 1863 but the community who had encouraged him to go with Mar Roccos now refused to accept him as he had been consecrated by the Nestorian Catholicos-Patriarch instead of the Chaldean Patriarch. They forced him to shave his beard, the sign of his elevation, and he return to work as a parish priest in the State of Travancore. The community in Thrissur, ignorant of Mar Abdisho’s return, continued to seek an East Syrian bishop.

Upon his arrival he enquired into the whereabouts of Mar Abdisho and found the people ignorant of both his existence and whereabouts. Eventually he was found working in his parish in Travancore and brought before the new Metropolitan where his priestly dress and lack of any episcopal accoutrements deeply distressed him. The Metropolitan recognised Mar Abdisho’s rank of Metropolitan by placing his own pectoral cross around his neck. It is important to realise that, although Mar Abdisho had been consecrated by the Nestorian Catholicos-Patriarch, Mar Mellus (under the renegade Chaldean Patriarch) not only recognised his consecration and rank but also his jurisdiction. Mar Abdisho then worked with Mar Mellus until the later was recalled to Mesopotamia eight years later after the death of the Patriarch by his successor. He was eventually reconciled with Pope Leo XIII in 1899 and died as Bishop of Mardin in 1908.

In 1875 Mar Philip Jacob Abraham was also sent to join Mellus by the Catholicos-Patriarch. He worked in Kuruvilangat and then in Thrissur until he was kidnapped in 1877 by the Vicar Apostolic of Bombay, Monsignor Meurin. When the laity sought out the Vicar Apostolic he engaged them in a debate about the term Theotokos, and then left with their bishop who returned home.

With neither Mar Mellus or Mar Jacob left in India Cor-episcopa Michael Augustine administered the East Syriac Rite Church while Mar Abdisho continued to look after his parish in Travancore. He only travelled to Thrissur for major feasts when the community had need of a Metropolitan or bishop. Mar Abdisho was engaged in a lengthy legal battle with the Roman Catholics over ownership of his parish. He lost the case in 1897 and without a parish or home he was invited to come and live in Thrissur. He accepted the offer and lived in Thrissur for three years until his death in 1900. His body was buried in the Altar of the Cathedral church where it remained until it’s translation in 1954.

Upon his death Cor-episcopus Michael Anthony proceeded to rule the church for eight years until, after his request to have a bishop consecrated for India was granted by the Catholicos-Patriarch of the East Mar Benjamin Shimun, and Mar Abimalek Timotheus arrived as Metropolitan in 1908. The Syriac letter answering Cor-episopus Michael Anthony’s request for a Metropolitan was drafted by the Catholicos-Patriarch’s Archdeacon who, as it happened, would be the very man sent to fill that post. The framed letter hangs in the entry hall of the Metropolitical Palace.

Mar Abimalek Timotheus was educated by the Church of England under the auspices of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Assyrian Mission, his tutors being The Rev’d A.J. Maclean (Later Bishop of Moray, Ross and Caithness in Scotland) and The Rev’d Dr W.H. Browne who was sent in 1907 by the Archbishop of Canterbury to Thrissur to ensure the suitability of the posting.

Mar Timotheus’s arrival as Metropolitan, though the realisation of a long held hope, was the cause of further tensions. He was enthusiastically welcomed by the laity but although Cor-episcopa Michael Augustine has requested the appointment of a Metropolitan for India he was unable to find it in himself to give up leadership. He thus insisted that Mar Timotheus was sent to succeed him and that he had no authority until he died. This strange view led the Cor-episcopa to issue a legal suit against the new metropolitan (suing one another seems to be one of the chief recreational activity of the Nasrani) just two weeks before he died.

The suit brought in 1911 lasted until 1925. The suit claimed: 1) that Mar Timotheus could only exercise authority after the death of Cor-episcopa Michael Augustine (rather a moot point as the latter was now dead) and; 2) that the new Metropolitan must conform to the current customs of the now ‘Independent Chaldean’ community and not change anything. This was significant because the worship in the cathedral, Mart Mariam Valiapally, did not conform with all of the Church of the East’s practices. For example, the cathedral had statues and crucifixes whereas members of the Church of the East abhor images and only display a plain Persian cross with no corpus upon it. They possess no statues and no icons. Although Mar Timotheus won the case in 1919 there was an appeal and so it was still dragging through the courts. The Anglican Principal of Saint Stephen’s College in Delhi suggested that Mar Timotheus approach the Maharaja of Cochin to issue a Royal Proclamation, if both parties agreed, appointing a Sole Arbitrator for settling the case. Both parties did agree and the Maharaja appointed the British Resident C.W.E. Cotton. In 1925 the British Resident awarded all property to Mar Timotheus. The ‘Independent Chaldeans’ gathered as a congregation looked after by the assistant priest of the Syro-Malabar Cathedral. Eventually they would go on to build a Basilica, named after the Cathedral they had lost, that has the highest church tower in south-east Asia.

Mar Timotheus served as Metropolitan of All India for over 37 years. He died in 1945 and was buried in the Prelates Mausoleum in Thrissur.

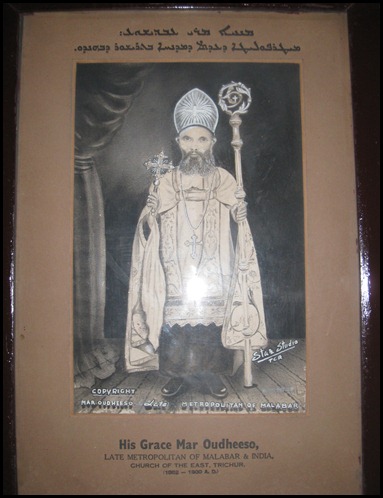

From 1945 until 1952 there was no bishop for the Church of the East in India. Finally after seven years the Catholicose-Patriarch Mar Eshai Shimun XXIII sent Mar Thoma Darmo as the new Metropolitan of Malabar and India. He had served in North Syria and was chosen by Mar Yosip Khananisho Metropolitan of Iraq as a suitable candidate for India.

In time Mar Thoma Darmo developed strong differing opinions to the Catholicos- Patriarch. The Patriarchal visit to India in 1961 only succeeded in increasingly the difficulties between them. In January 1962 Mar Shimun wrote to Mar Thoma Darmo appointing an advisory board for the administration of the Indian church. When it was explained that the Church in India already had elected Central Trustees established in law for the administration of the church the request was simply repeated. The Metropolitan refused to comply and the Catholicos-Patriarch suspended him in on the 10th of January 1964.

The major difference of opinion between the Catholicos-Patriarch and the Metropolitan centered on the issue of hereditary succession for the Patriarchate and the Episcopate. The Patriarchate had been held by the Shimun family since the middle of the 15th century passing from uncle to nephew in unbroken succession. This was also the case for the bishops and at this time mar Thoma Darmo was the only non hereditary bishop in the Church of he East.

When The Catholicose-Patriarch issued a universal order for the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in March of 1964 the strain was too great and the Church of the East split between the Old Calendarists and the New Calendarists. In September of 1968 the Old Calendarists elected Mar Darmo their Catholicos-Patriarch and he left India permanently. After arriving in Baghdad he consecrated Mar Poulose episcopa and Mar Aprem Metropolitan for India. Mar Darmo died in 1969.

Of course the split in India led to further lawsuits. The Old Calendarists were represented by Mar Aprem, who had returned to India after his consecration, while the New Calendarists only received a bishop in 1971 when a laymen was ordained to all orders and made Metropolitan. He arrived in Thrissur in 1972. Both the new Metropolitans were natives of Thrissur and Indians.

Attempts to reconcile the two groups was further confused when the New Calendarists patriarch abolished episcopal celibacy and then promptly married and thus was deposed. After his reinstatement he was assassinated by an aggrieved family member. In 1976 Mar Dinkha IV was chosen by the Holy Synod of the New Calendarists as the first non hereditary Catholicos-Patriarch for almost five hundred years. Interestingly for Anglicans, the Holy Synod for the election took place in Alton Abbey whilst the consecration took place in Saint Barnabas Ealing.

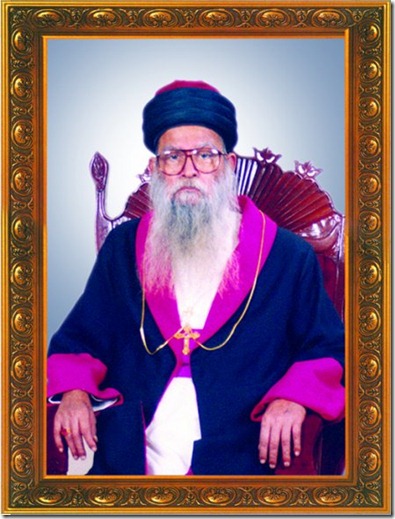

One of Mar Dinkha IV’s first actions was an attempt to end the schism in India. After failed attempts at arbitration he visited Thrissur himself in 1991 and was again unsuccessful. Finally after years of dialogue, litigation and negotiation the two groups were united in 1995 headed by Mar Aprem as Metropolitan while Mar Timotheus was made Apostolic Delegate to India, a post he held until he died in 2001. Mar Poulose had died in 1998.

This is a brief history of the Church of the East in Thrissur that brings us up to the present day. Like many excerpts from ecclesiastical history it is not very: romantic or edifying; seems to have little to do with theological or spiritual values but rather liturgical and ecclesiastical cultural differences; has much to do with power, property and authority; features many big egos and few humble servants; and is liberally salted with fights, litigation, and schisms.

For those of you disappointed by the mundanity of these details, all I can say is that the more and more widely I read about the history of the church throughout the world the more I find that this history of the Church of the East here in Thrissur is just a microcosm of much of the history of the church. The question of the problem of power and authority in the church stemming from an ordained hierarchy has been wrestled with from time immemorial. I need only point out that the problem has yet to be resolved and it affects all of us in episcopal systems. It is sometimes depressing to realise how much ecclesiastical history can simply be chalked up to ‘Bishop verses Bishop’.

The sociological and moral question of the widespread use of litigation amongst the Saint Thomas Christians is fascinating. Although Holy Scripture forbids Christians to take one another to court and provides an alternative dispute resolution process there does not seem to be much contrition or embarrassment that this is ignored and the secular courts are often one of the very first recourses. Please do not get me wrong, I am not claiming Anglican superiority on this issue just that most Anglicans are mortified by the present court cases over property and cringe ever time they are mentioned. Many believe that the episcopal and primatial leadership in the USA that has lost its moral authority because of its recent litigious behaviour. Still, it must be pointed out that litigation is a definite improvement on kidnapping and deportation.

I have asked about this issue directly and it is clear that the prevalence of court cases is not considered particularly shameful and I even believe I detect a note of pride when being told about the winning of certain historic cases. I do not have the knowledge or resources to deal with this question yet and if I do it will need its own post.

I am fully aware that one of the cultural stereotypes of Indians is their love of litigation. In no way do I accept or deny the factual basis for this stereotype and my comments here are solely based on what I have read about the Saint Thomas Christian community in India. To be more direct, don’t get annoyed with me for repeating a stereotype out of ignorance or without cause. Definitely don’t sue me.